Book review

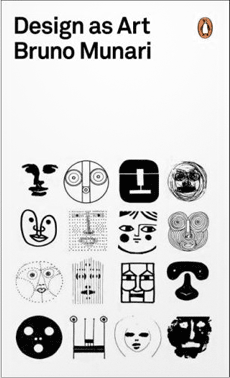

Design as Art by Bruno Munari

The ancient Japanese word for art is Asobi, but it also means game. I think this is how Bruno Munari sees art–not something exclusive to the halls of elite exhibitions, but something exploratory that involves the viewer as much as the artist.

The ancient Japanese word for art is Asobi, but it also means game. I think this is how Bruno Munari sees art–not something exclusive to the halls of elite exhibitions, but something exploratory that involves the viewer as much as the artist.

Design as Art is a collection of Munari’s essays on various topics concerning design and art–if there is a distinction at all between them, which Munari questions at the start of the book. These short essays, each two or three pages long, are grouped together under five areas: Designers as Stylists, Visual Design, Graphic Design, Industrial Design and Research Design.

I like these types of books because the ideas inside are just the right length. Unlike books where the author feels compelled to write long interconnected chapters, with the danger of padding things out and repeating themselves, here the short essays cover just enough ground to satisfy each thought and idea. The book was first published in 1966, though all the ideas in it are just as relevant today. There are also plenty of illustrations and photos throughout, and coupled with the variety of ideas, make the book a very enjoyable read. In-fact, I enjoyed it so much I got through it all in just a couple of sittings.

On stylists

Where we go wrong is we look at the world of art in art galleries, or the world of architecture of great old Renaissance villas, and we transfer it to our own designs for everyday objects. We decorate and style those objects in a superficial coat, that has no purpose other than to look attractive. It doesn’t express anything about the object itself, nor does it take on the qualities of the object–rather it covers the object with something external, a style that’s currently in fashion.

The problem with that is that styles tend to go out of fashion. By styling your design with the latest trend you put an end-of-use date on that thing you’re designing. The design of the object is no longer itself, it’s something external–something fickle.

The thing in itself

If we look around us we see a lot of art and design trying to represent something else. Art is trying to depict certain scenes of our own world and nature, design trying to mimic other objects. For example, Munari writes about how he visited a gift shop and saw an endless supply of imitation objects, “a photo-frame like a pocket watch, scissors like a flamingo, a salt-cellar like a wheelbarrow with a spoon like a shovel. A dish for fish shaped like a fish, a dish for pig’s foot shaped like a pig’s foot, a tureen for tomato soup shaped like soup. A hammer like a fish. a fish like a hammer, a cheese-dish in the form of a sitting hen, a thermo flask for ice, shaped like a football”. He concludes that, “these are certainly not objects produced by designers, for designers do not have such raging imaginations. They confine themselves to making candlesticks that look like candlesticks.”

In his view the role of a designer is to create the thing in itself, in the form of itself, not an imitation of something else. The form should be almost spontaneous, governed by the function of the thing and the materials used to create it. Other factors that will influence the design are cost of manufacture and transportation–important factors of industrial design.

Japanese design

Throughout the book Munari keeps going back to Japanese design, which he approves. The reason for this is that Japanese design is oftentimes exactly what I’ve described above: it’s designing the object as the object itself, and not an imitation of something else. Another important element of Japanese design is its close connection to the materials used–an intelligent use of each material depending on its looks and properties. As a result, Japanese design embodies the object with both, its function, and the properties of the materials used.

Take chopsticks. Two pieces of wood. The same pieces of wood can be served to anyone, regardless of their status, and regardless of the occasion. They are simply designed, light and easy to make. They are cheap and you can throw them out after a meal. The only prerequisite for their use is to cut up the meal into bite size pieces beforehand. Compare this to Western cutlery. You can buy all sorts of knives, forks and spoons. They can be cheap, expensive, steel, silver, funny, serious, light, heavy, and so on, and never mind the various utensils and knives designed specifically for different dishes, whether that be some Parmesan cheese, or a rack of lamb. Moving to a new house? You better make sure you’ve bought all the various cutlery you’ll need. The Western utensil is an explosion of complexity where as the chopstick is an eating tool reduced to its simplest form.

Useless machines

Throughout the book Munari introduces some of his own inventions, pieces of art he calls useless machines. For example, one such thing is something you would hang on the ceiling that’s made out of fine metal mesh, curved on itself several times over. The resulting object will wobble and rotate slightly as the air passes around it, but the real point is the shadow that it casts–something that looks like a pencil sketch due to the metal mesh pattern, but at the same time animated and flowing, like a cloud. It’s art that breaks out of the old two dimensions of paintings, and becomes three and four dimensional with the addition of time through animation. It is also spontaneous art–the object takes the properties of its material and produces something unique to itself with little direction from the artist.

Munari’s playful, experimental approach is interesting and inspiring, and reading through his examples has given me ideas for my own work. Although the book was first published in 1966, the ideas are very much applicable today. Overall, Design as Art is a very thoughtful, interesting and well written book that I highly recommend regardless of what type of design work you do.